The Three Service Rhythms

Part 2

By Doug Eng, EdD PhD

In the first article in this series we introduced the concept of rhythm style in serving, and identified for the first time, the three rhythm styles in the pro game. These are: the Abbreviated Rhythm, the Staggered Rhythm, and the Classical Rhythm. (Click Here.)

We saw differences in the way these rhythm styles correlated with the height of the toss, the point at which the player releases the ball, and the timing from the release to the contact, based on the study of dozens of pro video clips.

Now in this second article we'll investigate the consequences of each rhythm style for the rest of the technical elements. As you develop your service rhythm, it is important to realize that each rhythm has particular characteristics and effects that influence the rest of the motion.

These relationships between rhythm style and the other technical elements are far from absolute and their meaning at times may not be clear. But they need to be explored in understanding the complexities of the serve. Before doing that, though, let's start with a detailed review of the 3 variations.

Abbreviated Rhythm

The Abbreviated Rhythm is characterized by a shortened backswing. This means that when the server releases the toss, the racket hand is much higher than the other styles--as high as shoulder level or even higher. Typically the abbreviated serve has the lowest toss and the quickest delivery, meaning that it has the shortest interval between the ball release and contact. The tossing hand also releases the ball at the lowest point of the three rhythms. Andy Roddick, one the game's all time great servers, uses an abbreviated rhythm, as do Gael Monfils and Rafael Nadal.

So how do these basic characteristics of the abbreviated rhythm correlate with other technical elements?

First, abbreviated rhythm servers tend to use a narrow platform starting stance. Second, abbreviated servers rarely utilize a pronounced rocking motion or backward weight shift at the start of the motion. Third, in general these players have great, forceful upward leg drive. Fourth, the motion itself can also tend to have a hitch or pause.

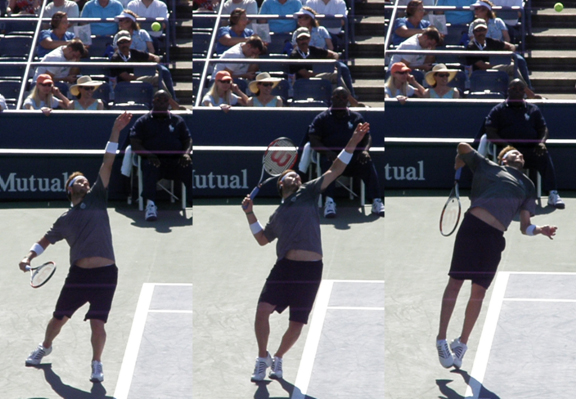

Staggered Rhythm

The second rhythm type is what I call a Staggered Rhythm. This means the toss happens when the racquet hand is much lower, down near the hips. Jo Wilfred Tsonga, Tomas Berdych, Robin Soderling, and Venus Williams are all examples of staggered rhythm servers.

As we saw in the first article, staggered rhythm servers have the highest tosses and release the ball at a higher point than the other two variations. The motion also tends to be continuous without any hitches.

Staggered Rhythm servers typically begin the motion with wide starting stances. They have a pronounced backward weight shift, and often use a back and forth rocking motion. In general, they tend to slide the rear foot upward toward the front foot, into a pinpoint stance. In extreme cases, the rear foot can also slide to the right of the front foot. Finally, staggered servers tend to get further into the court at contact.

Classic Rhythm

In the classic service rhythm, the hands move down together and then up together. At the toss, the racket arm tends to point backwards away from the body, with a height in the mid torso range. Andy Murray and Roger Federer are classic rhythm servers.

Classical rhythm servers tend to start in moderate stances of intermediate width. From this position they can keep the rear foot in position using platform hitting stances. But they can also slide the rear foot forward into the pinpoint. Like the abbreviated servers, their motions can also have a hitch or pause.

Those are some general characterizations. But now let's discuss these and other technical factors in more detail, and explore some of the complexities and varieties in the way players combine them.

Rocking and Weight Shift

Let's start with the controversial question of weight shift at the start of the motion. It is often argued that player's rock their weight back and forth at the start of the motion to initiate more force pushing off the ground. In reality many tour level players don't use this initial weight transfer.

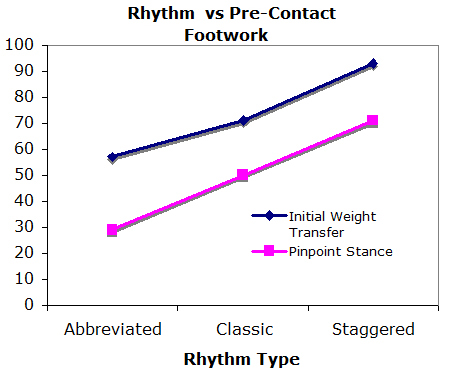

The chart below shows the relationship of rhythm style to initial weight shifts. The smallest pre-contact weight shift occurs with the abbreviated rhythm, the most with the staggered, with the classic in between.

There are two reasons that the abbreviated rhythm has the smallest backwards weight transfer. First, the initial path of the racquet is upwards which keeps the racquet and arm close to the center of gravity. Second, many players with the abbreviated motion tend to stand with the feet very close together, which is not conducive to significant rocking between the feet.

This means the forces generated along the length of the court are probably less. But the upwards force does not seem to be compromised, and may in fact be increased. In general it is probably fair to say the abbreviated rhythm generates relatively less linear force into the court and more horizontal force upward toward the ball.

The greatest weight transfer to the back foot occurs with the staggered rhythm servers. We see some players emulate Pete Sampras by lifting the front toes, which creates a natural loading of weight on the back foot, and then combining this with a platform stance.

But usually in the staggered rhythm this initial backward weight transfer is followed by a weight shift to the front foot and the use of the pinpoint stance. This means that in general the staggered rhythm probably creates some linear momentum.

Why does this rocking happen? If you keep your racquet down by your side when you toss the ball, your weight will natural shift backwards. Then, at some point, you must recover and shift forward. Once you start rocking the cradle, it perpetuates motion and linear momentum. As a result, the pinpoint stance may naturally happen.

It's important to note that this is a general tendency and not an exclusive one, since there are some players (20-30%) who vary their footwork outside this pattern. This includes Pete Sampras, who has a slightly staggered rhythm and a platform stance. Fernando Gonzales is another significant exception. But in general, the platform stance was correlated better with the abbreviated or classic motions.

One factor here seems to be the width of the starting stance. Once the spacing between the feet becomes large enough, the shift to the pinpoint after the initial backwards rocking is probably inevitable. Mardy Fish is a classic example of a Staggered Rhythm player with a wide starting stance who uses the pinpoint.

Another important technical point is that the staggered rhythm also creates increased backwards tilt with the shoulders. For staggered servers, the tossing arm is well above shoulder level while the racquet arm is still down by the side of the body.

In contrast, the abbreviated rhythm involved an initial upwards movement with the arms which limits weight transfer to the back foot. Because of this, it does not seem natural to bring the back foot forward into pinpoint stance. This is why players using the abbreviated rhythm tend to take a narrow platform stance.

It is important to realize that actual forces generated--whether linear or horizontal may not be only or mainly dependent on the initial weight transfer. They may also be a function of parameters such as knee flexion.

Although the abbreviated rhythm might appear to concentrate more force upwards, with sufficient knee flexion, hip tilt, and rotation, the staggered rhythm could also produce great upwards forces. Additionally, rocking backwards may explicitly put weight on the back foot, but bringing it forward into the pinpoint stance may actually reduce the amount of upwards force it generates.

It is also possible that if some weight is kept on the back foot, as in a platform stance, it may provide more force off the ground. The fact that many touring pros don't visibly rock back does not mean they don't utilize the ground with the back foot. When the foot is already anchored with additional knee flexion, this could be a better indicator of upwards force.

Into the Court

Now let's move to the final two technical issues: where the players land in the court and the location of the contact point. How high and far can players reach into the court? Obviously there are physical factors involved, the player's height, reach, and even racket length. But our question is: do certain rhythm styles lend themselves to increasing this reach?

The question is complicated by the issue of hitting stance, since players with a particular rhythm style don't all use the same stances. So let's break it down by looking at the landing point and the contact point independently.

We might hypothesize that the rhythm style which best loads weight onto the back foot would produce the greatest linear momentum forward into the court. If so, then the landing step into the court might be the farthest. The results seem to bear this out for the men, but are not consistent for the women.

For the men the staggered rhythm produces the greatest first step. But for the women, the abbreviated does. Interestingly, for both men and women, the classical rhythm scored the lowest. The chart summarizes the findings.

Rhythm Style and First Step |

||

| Rhythm Type | First Step (inches) | |

| ATP | WTA | |

| Classic | 15.7 | 11.0 |

| Abbreviated | 20.0 | 21.3 |

| Staggered | 21.9 | 17.7 |

Stances

But if we look at landing in another way it in terms of stances, rather than rhythm we see yet another picture. Here the platform stance scores highest for the men. But again this doesn't hold when we look at the women, where the platform produces the smallest first step. Again here is the chart.

Stances and First Step |

||

| Stance Type | First Step (inches) | |

| ATP | WTA | |

| Platform | 23.8 | 13.0 |

| Narrow Platform | 19.5 | 18.0 |

| Pinpoint | 21.7 | 17.4 |

It also appears that a combination of the classic rhythm and platform stance may be the most difficult to get far into the court. However, it is hard to draw any conclusions with the abbreviated rhythm in part since that was the smallest sample size.

Contact Point

So let's look at it a third way, by looking not at the landing, but the contact point.

Is rhythm style related to how far into the court the player's make contact, as opposed to where they land? The table illustrates the results. Interestingly by this measure the staggered rhythm produces the most reach into the court at contact for both the men and the women.

Reach of Contact Point Into the Court (Inches Past Baseline) |

||

| Rhythm Type | ATP | WTA |

| Classic | 17.9 | 13.0 |

| Abbreviated | 16.6 | 17.3 |

| Staggered | 22.9 | 17.7 |

So our study produced some interesting correlations but further understanding is probably needed to clarify the relationships between rhythm, stance, landing and contact. One factor to consider may be the toss. It is possible the position of the ball could account for differences in how far the player contacts the ball over the court and where he lands. And when we see great servers such as Sampras, Roger Federer, or Greg Rusedski land less far into the court than many others, we may ask whether a relatively farther landing is truly an advantage.

Balance

Another very interesting aspect to consider here is how the body balances itself depending on where the player lands. If you examine those players who land the shortest and farthest into the court, you will see a significant difference in how they balance themselves. The players who land the farthest into the court often have a high back kick to create balance as they lean forward on the follow-through. This can be an important point for any player in developing their motion.

Gender and Rhythm

A few additional thoughts on the differences between the men and women. Many coaches have observed that the majority of women players use the pinpoint stance. There is a belief that the number of double faults some players hit is related to this.

This is because the pinpoint stance promotes early opening of the hips, less hip tilt (resulting in less shoulder tilt or shoulder-over-shoulder angle). It probably also reduces upwards force generated with the back leg. That in turn reduces the amount of spin one can apply on the ball. (Click Here to read John Yandell's analysis of Jelena Jankovic's motion dealing with this issue.)

In our study, roughly 90% of the women players we looked at did in fact use the pinpoint stance, and a high percentage combined this with the staggered rhythm. Venus Williams is a good example of this combination, and also a player known for serving high numbers of double faults at times in tour matches. If you watch her motion, you will note the reduced hip and shoulder tilt and early opening of the hips. Venus's torso is usually parallel to the baseline at contact.

On the men's side, players tend to be split between the classic and the staggered rhythm. They also tend to be split between the platform and pinpoint stance. Although heavily scrutinized as of late, the abbreviated rhythm still hasn't gained popularity among the majority of tour-level players.

Like the women, there was a tendency for men using the staggered rhythm to also incorporate the pinpoint stance. Men using the classic rhythm tend to be split between the platform and pinpoint stance. Although you can find examples of men players who are more open at contact, the problem is less pervasive on the men's side, with most players at least partially closed at contact.

Conclusions and Questions

So these first two articles have introduced a new way of categorizing the serve, and studied the relative correlations with many other variables. In some areas, we have raised as many questions as we have answered. And further study of the meaning of rhythm styles is definitely in order. But in the next article, let's turn to practical questions. As a player or a coach, how do you decide between rhythm styles? If you are using a certain rhythm style what are the possible problems, and what can to do to work on and improve the motion? Stay tuned.