The All Court Game

William T. Tilden II

|

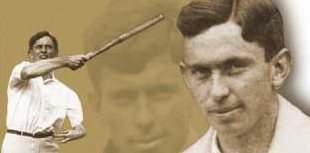

| William A. Larned, the original baseliner. |

Modern tennis is the equilibrium of the pendulum after two long swings. It is the sound, sane, sensible combination of the best tennis of all periods.

What is this all-court game? What does it include? First, I claim it must include all the standard strokes; service, both slice and twist; drive and chop, both forehand backhand, volley and smash. Second, it must include varied depth. No longer will consistently deep driving prove a satisfactory standard. Today one must vary distance as well as direction. The short shot has its place in modern tennis just as much as the deep one. Third, the all-court game demands varied spin of the ball, with which to change pace.

Every player must be able to both undercut and topspin his ground shots. Fourth, there must be controlled speed. Please note the word "controlled." Speed alone will not suffice; it must include sufficient control to vary it according to the opponent you face. If I were to attempt to define the all-court game tersely, I should say: you must be able to vary your game at will, both as to direction and depth, speed and spin.

|

Maurice McLoughlin, the miracle of speed and net attack. |

Development of the All Court Game

The original growth of tennis produced the baseline driver, culminating in our greatest baseliner, William A. Larned. But it was during the last dozen years of this period, which ended about 1911, that experimental minds in the game were working along the lines of the net attack. The game was still essentially baseline driving, with the cry "depth" as its slogan. Anyone who drove within less than five feet of the baseline was looked upon as hardly worthy of consideration, yet speed as we understand it today, blinding, battering, crushing, was unknown.

Then came the miracle on the side of speed and net attack. It was Maurice McLoughlin, he of the red hair, gleaming smile and pulverizing punch in service and smash. He swept the country. He revolutionized the game. During the years 1912, 1913 and 1914 when McLoughlin was in his prime, speed ran rampant through the tennis world. Everywhere players discarded their ground games to adopt a fast service and a smashing net attack. Safety was an unknown word in the tennis game in the United States. The god Speed was at the wheel, driving the game on to danger.

|

Norman E. Brookes, the Australian all-court player. |

Then came another reaction, exemplified in the person of Richard Norris Williams II. This young American was recently re-turned from his studies abroad, his tennis obviously influenced by the modern trend of the rising bounce style of the European game. But Williams carried the European style about two steps further in and played every ground stroke off the rising bounce. Williams was essentially a baseliner, but a baseliner who played two feet inside the baseline, instead of ten feet behind it like the old stars. He was the connecting link between the passing style and the one to come.

It was during the period just before the war that one figure appeared who in my opinion was far ahead of his time. This man was Norman E. Brookes, the Australian wizard. When other players knew nothing of the all-court game Brookes was playing and studying it with a certainty and knowledge which we today may well be proud to some day attain. It was Brookes who developed the perfect balance of the two styles in actual match play. Brookes was our first real all-court player.

William Johnston

It was 1915 that saw the national championship rest on the brow of a man who was destined to point the way to the modern, sane, and to my way of thinking, correct game of today. William M. Johnston, also a Californian, swept to victory in 1915, beating both Williams and McLoughlin by the solid, sound, defense and the powerful punching offense of his all-court game. The period from 1912 to 1917, when the World War put an end to sport, was one of change and uncertainty, with Johnston the rising figure by virtue of his all-court style, Williams slipping slightly, while McLoughin faded from the picture.

|

Little Bill and Big Bill before a match. |

Then came the close of the World War and with it the revival of sports, particularly tennis, the world over. New figures had risen during these few years while others had passed on. Since the war new all-court stars have gained prominence. A new era seems even now peeping around the corner at the all-court game. Vincent Richards, Henri Cochet, Rene Lacoste, Manuel Alonso and Brian I. C. Norton are the most notable examples of the all-court game, plus something new.

It was during the years after the war that I was gradually gaining mastery of my varied strokes and proving, what I had always contended, against great opposition - that no player can have too many strokes in his equipment. Even as a boy I was a believer in the varied, all-court game, yet during the years I was experimenting with the different strokes I was told repeatedly and vehemently that I was crazy, that I was working along the wrong idea, that I should concentrate on one style and play it, that I could never learn to both drive and slice, that, all in all, I was a typical dub.

For years this last estimate appeared correct, for I was indiscriminately and monotonously defeated. Finally the turn came, and with the years since the war I have trod the uppath.

|

Big Bill: Troding the Upath with the all court game. |

Future in the Forecourt

What is the future of the tennis game? Have we reached the ultimate development of the game in the champions of the present? As one of the champions of today, I see vistas of progress ahead, of which I glimpse only a bit, but which the champions of tomorrow will have explored and developed.

Where are these lanes of progress? Not from the backcourt. Not from the net. It is rather in the use of the forecourt for sharp angled shots, in the use of the mid-court volley, the half volley and rising bounce shots, that future progress lies. Every player who desires to succeed in the future must equip himself with every shot in tennis and then strive to explore the mysteries of the forecourt.

Yet at this time, when I am speaking of the last word in tennis technique, the ultimate in stroke production, let me for a moment sound the warning that on the rock of first principles the new game must be built. You cannot learn the fine points without complete mastery of the fundamentals.

Most players slur over the importance of that cardinal point, without which modern tennis, in fact any tennis, is impossible. Keep your eye on the ball and keep your mind on the game. It is impossible to overstress these points. Fully 95 per cent of errors are due either to not watching the ball, or to lack of attention to your stroke at the moment of making it.

The greater the diversity of stroke, the more varied the spin, speed and direction of a player's game, the greater the chance of error, and therefore the more important that he should keep his eye on the ball. Any player may learn strokes if he has mastered the secret of watching the ball, but the greatest stroke player in the world will go down to defeat if he allows himself to grow careless in the fundamentals of the game.

The future lies ahead with its tantalizing glimpses of unexplored roads of progress. Would that I were not an old dog who finds it hard to learn new tricks, for I would gladly attempt to explore some of these roads. In fact, I may try it anyway. The young stars have their chance. To them I say, go out into the highways and byways of the game and bring back, developed, those interesting but imperfect shots that today lie on the edge of our modern tennis in its all court games.