The Accidental Volley

William T. Tilden II

|

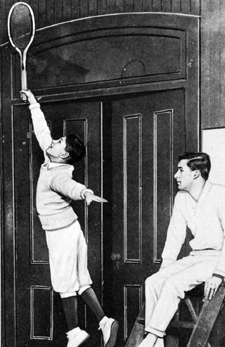

Big Bill with his protege and future doubles partner Sandy Weiner. |

Accidents sometimes prove a blessing in disguise. One could hardly recommend the loss of a finger as a definite asset to a tennis player. Yet, strange as it sounds, I owe a marked improvement in my net game, volley and smash to the accident of the loss of my middle finger of my right hand. I had been too soft in my volley game and overhead. I always knew that. Yet somehow or other, in the days when I had all my fingers, I never could drive myself to kill. (Editor's Note: Tilden lost the tip of his second finger to a severe infection that almost cost him his life.)

In 1922 I met Sandy Wiener, and the boy and I started to play doubles together. Then, late that year, came my accident and the resultant loss of my finger and what, for a time, seemed to be the end of my tennis. Finally, with the Spring of 1923, I began my attempt to come back. I quickly discovered that certain soft shots of finesse that I had formerly relied upon at the net were gone from my game forever. Sandy and I were once more playing doubles, but my lack of finishing shots had us in trouble, since the boy was then too young to play on even terms with the rest in fast company, a condition which he remedied in 1924, when he jumped far up the tennis ladder.

I discovered that either I must learn to volley decisively and smash to kill, or Sandy and I would meet far more defeats than pleased either of us. Once more I found myself facing intensive practice, this time from necessity. All through the season of 1923 I pounded away at my volley and overhead. Naturally, I found the loss of my finger had affected my grip on the racquet and that it turned in my hand quite often. This increased the need for a speedy win of a point. I could no longer rely on my ability to outsteady my opponent. I must hit for a winner at once.

|

Although he was lucky to survive, the infection cost Bill part of his middle finger. |

Gradually my incessant work on volleys and overheads began to pay dividends. I actually reached a point when I was reasonably certain of winning at the net. I gained confidence, and with my confidence grew my effectiveness. I have always felt that the keynote of success against Johnston in 1923 and 1924 was the fact that on crucial points, when I advanced to the net, I could win outright if I could place my racquet on the ball at all.

I feel that I owe my improved volley and overhead to Sandy Wiener and to the loss of my finger. I will never be a great volleyer and smasher. I know that. I have not the genius for the net game that characterizes Vincent Richards or Bill Johnston. They are my superiors in every department of the volley and smash, but, at least my intensive practice, so unusually forced upon me, raised my volley game to new heights.

There seems much of conceit in this story of personal progress. I do not mean it as such. It is the lesson to be learned from these two steps up the tennis ladder that is my excuse. What I did, with this degree of success, many other players with far greater natural talent than I, and there are many, for I am a handmade tennis player, can do with better effect and in less time.

Intensive practice over a period of some weeks will fill many a gap in the game of players who today are plowing through the disheartening period of the "almost-great." There are many players who are handicapped by some glaring hole in their game which, unless remedied, will always chain them to the second flight.

Sometimes a player is called upon to face a serious problem, when, too late, after habits of poor stroke productions are formed, he finds himself face to face with the question of his future development. If he continues his old methods, he has little or no real future in the game. He may make the First Ten, or he may not; but he will never be a serious aspirant for Championship honors.

On the other hand, if he discards his old style and sets out to learn a new, sound one, he runs the danger of ruining his old game and never mastering his new one. He takes a gamble on the possible Championship against tennis oblivion. It is a serious problem. Sometimes a word of advice at the right moment, even if it seems unnecessarily severe, will start a player on the road to progress.

The day of the player with a lop-sided lame is over. Today the champion cannot afford to show weakness. Tomorrow, he must have even greater strength. If there is a hole in your game, plug it by intensive practice. Do not worry about the defeats you must bear during the time your game is developing. Go out to make of yourself the greatest player that lies within the range of your natural abilities and your opportunities. There is far more pleasure to tennis if you have no fear about your strokes. There is no sensation more thrilling than the impact of the ball on the strings of a racquet as a perfect stroke turns it back against your opponent.