The Birth of My Backhand

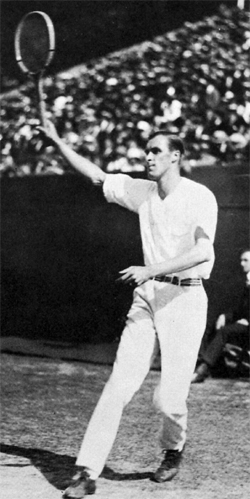

William T. Tilden II

|

An attacking backhand drive developed late in his career, through intensive practice. |

One becomes very weary of the cliches of one's youth that have been driven down one's throat. Take the old standby, "Practice makes perfect." Nothing, not even practice, makes anything, or anyone, perfect. Yet hidden in the dear old bromide is a bit of sound tennis advice. Practice may not make perfect, but believe me it has made many a good tennis player.

I am a great believer in practice, but above all in intensive practice. My idea of intensive

practice is to pick out one stroke and hammer away at that shot until it is completely mastered. My greatest

success with this system was the development of my own backhand, from a feeble defense chop to an offensive

attacking drive, through the intensive practice of one winter and at the cost of many lickings.

My backhand was born in the Winter of 1919 and 1920. Its place of birth was Providence, Rhode

Island. My backhand reached this earth because the United States was to challenge for the Davis Cup in 1920

and the Davis Cup Committee indicated to me that I would be considered seriously for the team that summer.

Up to and including 1919, my backhand had been a shining mark at which anyone could plug away with impunity.

|

The slice backhand alone was not enough against Billy Johnston. |

Billy Johnston had smeared it to a pulp in 1919. The many errors off my backhand lived clearly in my memory, and when the announcement of the challenge for the Davis Cup was made public, and it was intimated to me that I might go abroad with the team. I determined that if I went I would leave my old backhand in the United States and take a new one with me.

It is no easy job to learn a new stroke in three or four months, particularly when it is a new trick for an old dog, yet it had to be done. My first step was to work out a sound grip, swing and footwork, not a very difficult thing to do in theory, but once worked out, more difficult to put it in practice. There came the amusement for every one but me. Four times a week, sometimes more often, I would do battle on the indoor court in Providence owned by J.D. Jones, playing against him, his son Arnold, and several others. Every shot I could play backhand, I played backhand.

I intended to learn a drive, and drive I did. Only the walls or the net could stop my efforts during the first weeks. Far and wide went my shots, yet even at the darkest moments, when I was ready to burn my racquets and quit the game--and these moments were not infrequent--I would make one beautiful shot once in a long while that gave me courage to go on. It would prove by its very effectiveness that I was on the right road, and that only the mastery of the mechanics of the stroke stood between me and my new backhand.

Week by week I saw my backhand grow. Sometimes I would think I had lost it; the touch would go

for days at a time and I could not hit the ball in the court; then back it would come again, better than before.

Over these weeks my pride suffered many a humiliation. It is not particularly enjoyable to a Davis Cup candidate

to be repeatedly defeated by a veteran who had virtually retired from active tennis some years before, and by

his son, a junior player . Many a defeat at the hands of both I swallowed and laid these defeats--often not

too silently--on the altar of my backhand drive.

|

Tilden believed his new backhand drive resulted his championship titles. |

Gradually the turn came. I began to gain control of the new shot. It seemed to me that, in a period

of about ten days, the work of the whole winter crystallized and my game jumped ahead a full class. I played better

tennis, in certain ways, than I had ever played before in all my life.

It is true that certain other shots suffered by this concentration on the backhand drive, but they

came back quickly because I has the foundation for them. I had held myself steadily to hitting my backhand hard,

and I found that this steady punch had a tendency to speed up my entire game.

I was gaining in aggressive tactics.

Most players are not willing to devote more than a week or two at the most to the mastery of a stroke. If they have not the desired result then they usually let it go with a shrug. "What is the use?" they say. Well, possibly they are right; yet it seems a shame to me to pass up the ability to do anything well, simply because the effort seems tedious.

Strokes cannot be learned in weeks, they must be reckoned in months, and actual progress in years. I have never regretted the hours, days and weeks that I spent to acquire my backhand drive. To it, and it primarily, I lay my championship titles. I am convinced that had I not done the work necessary to master that stroke, Johnston would have continued to defeat me just as decisively after 1919 as he did .that year.

I do not mean that 1920 saw my backhand drive complete. Far from it. I worked and am still' working on it, as on all my strokes, for they all can stand development. The daily practice Johnston and I had against each other in New Zealand in 1920 and 1921 was also responsible for the solidification of my game, yet all the tennis I have played would not have produced that backhand drive if I had not put in the period of constructive, intensive training in 1920 in the indoor court in Providence.