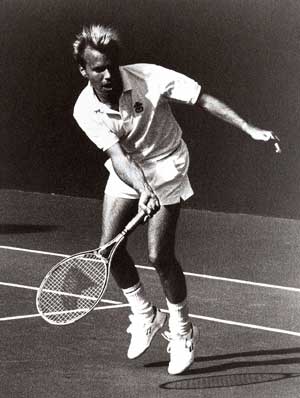

Playing John McEnroe

By Trey Waltke

|

McEnroe was like a shark. If he smelled fear he was all over you. |

What is it actually like to be on the other side of the net from John McEnroe? In 1981, I drew in the first round of the U.S. National Indoor Championships in Memphis . I had no delusions: He was better than me, which meant it was critical to think about the right game plan if I wanted to play the best possible match.

And here's the lesson, no matter what your playing level: Preparing for a match isn't a matter of blindly thinking about how you're going to hit 60 winners. Planning to win requires thoughtful analysis of how your game appropriately matches your opponent's.

Here's what I thought about me versus McEnroe. In 1981 he was already on his way to becoming a legend. But he was still human after all. Like all players, McEnroe had lost matches before and has his share of weaknesses. So my challenge was to hone in on finding those weaknesses and exploiting them as much as my particular style would permit. Maybe this realism comes from having grown up in Missouri , an austere place also known as the "Show-Me" state.

Playing McEnroe, or any player at that level, makes you hyper-alert. That awareness is mixed with the fear that if you don’t impose your game on him promptly, you could lose quickly and embarrass yourself in front of a lot of people.

It’s vital never to show how worried you might be. Players like McEnroe are sharks. The minute McEnroe smells fear, he’s all over you. But if you don’t reveal a single emotion, you can get your opponent a bit off-balance. After all, he’s not a mind reader and for all you know, he might be a bit scared of your own tools. Experience has taught me that you can never tell how two players will match up until they actually play one another. Everything from pace and spin to movement, shot selection, and the competitive aura each player exudes on the court figures into this.

|

If you hit with pace, John’s first volley was phenomenal. |

The first time I saw McEnroe play he was still a junior. His game looked flimsy, too dependent on his superb hands and less reliant on fundamentals. This was particularly true with his groundstrokes, especially his forehand. Even his backhand didn’t seem that strong, mostly a short stroke he pushed around the court.

Then, the next summer, John McEnroe went right from his high school graduation to the Wimbledon semis, instantly creating the aura of a champion. On the one hand, we on the circuit were shocked by his utter lack of respect for anyone on the tour. At the same time, we were awed by his skill at pulling it off. In the fall of ’77, I played him in doubles. Word had it he was even better in doubles than singles, so now, playing at the Los Angeles Tennis Club, I had the chance to experience it first-hand.

McEnroe was a doubles genius. He was hitting shots I’d never seen from a pro -- curving low lobs, wickedly early angled service returns, midcourt swinging volleys. He’d stand practically in the middle of the court, daring me to out guess him on my return of serve. It was precisely the kind of brilliant movement and ballstriking that could instantly take you way out of your game.

But again, even versus a genius like McEnroe, you must look beyond the artistry to the craftsmanship. Even the brilliant McEnroe had preferred patterns. For example, he had a great serve to the backhand in the ad court. My response: put my left foot in the alley when receiving so as to make him feel he had a smaller space to serve into. I wanted him to know that I was ready to play a backhand return - my strong side. And at the same time, I was daring him to hit the serve down the center - a shot that's more difficult for lefties.

|

If you got your first serve in, Mac wasn’t as aggressive with his backhand return. |

Granted, McEnroe hit the center serve as well as anyone, but at least by stepping into the alley I was letting him know that it wasn't going to be so easy for him to play that classic lefty combo of the swinging wide serve and the angled backhand volley. Making a guy play shots or sequences he'd rather not play is a great way to at least attempt to establish a toehold.

Another thing I noticed was that McEnroe’s first volley was phenomenal if you hit the return with pace. On the other hand, if you were able to get his serve back with a low, off-pace return, his tendency was to float the half-volley back to you and then, almost as a bluff, he’d close in on the net. Standing in like this off a weak shot left McEnroe vulnerable to quick lobs over his backhand shoulder. So again, I knew I’d need to take a lot of pace off my return and just get it down low at his feet. Not easy, but actually, for me, that soft, slice backhand was one of my favorite shots.

Serving to McEnroe also offered a few possibilities. He didn’t crack his backhand very offensively if you got your first serve in. This made me concentrate very hard on getting first serves in because he loved attacking second serves. Likewise, his groundstrokes didn’t always penetrate, so you had to keep hitting your own deep in order to elicit a short ball and force him to pass you.

You also had to account for the fact that at some point during the match, especially if the match wasn’t going his way, he was going to stop your momentum by throwing a tantrum, yelling at an umpire or even retying his shoes just before a critical point.

|

|

On grass John was virtually unbeatable. |

|

There was also an emotional aspect. The winner of our match was supposed to play a local teenager named Jimmy Brown. Everyone figured it would be McEnroe and Brown in the next round. I didn’t like that at all. Would you? Once you’ve done the rational stuff, there’s something to be gained from letting anger motivate you too.

Granted, the tiny holes in McEnroe's game weren't always there, but at least my homework gave me a few rungs to hang my hat on. But it's sure better to try and win with a couple of basic tactics than delude yourself into thinking you're going to suddenly hit dozens of winners.

|

I hadn’t planned fro Mac’s choice string of obscenities from point blank range. |

This brings up a point I try to teach juniors: winning tennis is usually boring tennis. To beat someone of equal or greater ability, you must be willing to do whatever it takes over and over again. Too many juniors get caught up thinking they have to beat someone with big winners. The object is to find that small chink and patiently drill at it at like a dentist slowly filling a cavity. And everyone's got some teeth that are weaker than others -- even John McEnroe.

That night in Memphis , I won 6-3, 6-4. From the time he walked on the court, I sensed McEnroe was preoccupied, not quite paying attention to how he was going to actually win rather than let his aura do it for him. So this gave the shark in me a little blood. As anticipated, he began stalling – a sure sign I’d at least made a dent (McEnroe never stalled when he was winning handily). After the first set, I knew the second set would have even longer periods of stalling, so I made sure to keep myself focused and never get bogged down in John’s negative energy.

Our next match came two years later, in Las Vegas . I applied the same strategies, and was able to scrape out another victory. Now again, I’m not going to say I was a better tennis player than John McEnroe. It was just a matter of styles and moments. And there was one more moment to come.

We played our final match later that summer in the first round of the U.S. Open. I took a two sets to one lead. McEnroe was livid. This wasn’t just another Memphis or Vegas. This was the U.S. Open.

The stadium was teeming with that buzz: a top player was in trouble. When you’re younger, these opportunities for big wins are tricky. A few years before, playing a tight match against Adriano Panatta at the Italian Open, I was oddly afraid to grab the big win. But now, against McEnroe, I knew that I’d beaten him before, and I wasn’t scared to beat him again. He knew this too.

|

Although I beat him twice, I felt Mac was the better player, a quicker more talented version of myself. |

So early in the fourth set, on a changeover, he got about one inch from my face and spewed out an incredible string of choice obscenities. I’d planned for him stalling, but even this I hadn’t planned for. Along with Pancho Gonzales and Jimmy Connors, McEnroe was that rare player who could get better when he got angry. It got me a bit off-balance. But more importantly, the way he played validated the lesson of this story: you must understand your game and understand what makes you win.

As the fourth set got underway, John began paying more attention to covering the court – and in short order, he began swarming me with lots of first serves, solid volleys and consistent returning. Those little mistakes that had cost him earlier in the match vanished. The last two sets went to McEnroe, 6-0, 6-1. I’d tried hard, but in many ways, he was just a quicker, more talented version of me – too tough.

For all the talk about McEnroe’s creativity and touch, to me his real genius was his ability to play aggressive percentage tennis. When they’re in trouble, great players don’t just start flailing. They’ll attack, but they’ll do so in a very buttoned-up way. Playing within yourself means never going for more than you need to. McEnroe was a master at this.

Still, whether in victory or defeat, the lessons I learned playing McEnroe apply to anyone: Don’t get overwhelmed by your opponent’s aura. Assess his game logically. Study patterns. Find ways to make your opponent play shots they don’t like, hopefully by hitting the shots you like hitting. Run the same boring play, again and again – because there’s nothing boring about a victory. And the next time you hear someone say, “I just didn’t play my game,” make a mental note to congratulate their opponent for not letting them.