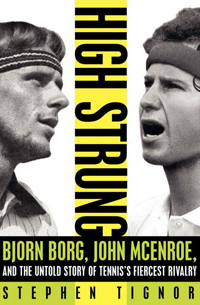

Mr. Nasty: Part 1

Steve Tignor

It was late on the second day of the 1981 U.S. Open, and the wind had begun to kick up. Many of the 8,000 or so fans scattered among the upper reaches of Louis Armstrong Stadium had been drinking. There was one more first round match left to see, and they were hell-bent on seeing it, so they began to climb down and fill the empty seats closer to the court.

When one of the players, a long-haired 22-year-old from the Kentucky backwoods named Mel Purcell, appeared, he was greeted with a beery big-city salute. "Nice headband, ya sissy!"

Purcell may have been a country boy, but he wasn't used to this treatment in New York. In his few visits, he'd become a fan favorite. "Give 'em hell, Mel" was a common cheer, and the fans loved it when he walked out for one match in a New York Mets batting helmet.

But on this night, Purcell was scared of what might happen to him. He was scared of the crowd; but he was even more worried about his opponent.

"I've never been so nervous for any match," Purcell remembers. "You never knew what Nasty was going to do next. And I knew 90 percent of the fans were going to be for him."

His opponent, "Nasty," was Ilie Nastase, a 35-year-old Romanian who had spent more than a decade playing the part of tennis's village loon. Two years earlier at the U.S. Open, he had added a new role to his repertoire: “Prince of Darkness."

In a 1979 night match against John McEnroe before an audience that, as McEnroe would later say, "had had a few pops," Nastase managed to get himself defaulted, have the umpire removed from his chair in a savage hailstorm of boos, start a near riot, get himself reinstated, engage in two sets of the finest tennis of that year's tournament, and finish the evening by losing for a second time-all while doing little more than standing around being Ilie Nastase.

On this day, as another set of similarly lubricated fans clambered down into their seats in the same stadium, Purcell thought back to that match and shuddered. Nastase's presence already seemed to be inspiring bedlam. A voice howled, "Go back to Kentucky!" It was going to be a long night.

As wary as Mel Purcell may have been, he knew he wasn't facing the Nasty of old, either as a player or a villain. Earlier that week, Newsday had summed up the state of the Romanian's game and life bluntly: "Nastase: Not Great or Nasty Anymore."

Fifteen years on tour had taken their toll. He had won Grand Slam titles and played with a high-strung grace and genius virtually unmatched in the sport's history. Also unmatched was the crassly hilarious boorishness with which he behaved.

He was perpetually frazzled, and his conduct knew no boundaries. In fact, it had been Nastase who forced tennis to put some boundaries in place for the first time in 1976 by implementing a "Code of Conduct," with penalties for hideous manners.

The sport had never had to deal with someone who, if he was in the mood, could transform a match into a cross between a comical New York traffic argument and a sporting version of a play by Beckett.

Open tennis had promised more color and personality from its performers, but it hadn't promised someone with quite as much of either as Nastase, whose act was always perilously balanced between the charmingly cheeky and the unpleasantly crude. Hectoring umpires, bantering obscenely with fans, imitating and insulting opponents--he called Purcell porcello, Italian for "pig"--yet making magic with his racquet, he was the living symbol of the circus that tennis had turned itself into when it entered the marketplace.

The Open era, and all of the new possibilities it offered players, appeared to have sent an electric shock through the man. Nastase had shown up on tour in the mid-1960s looking like any other amateur-era choirboy in all whites, with his hair neatly trimmed and parted at the side.

Painfully shy arid skinny, he seemed to be little more than a sidekick to the older Romanian player Ion Tiriac. If the sport had remained a leisurely backwater, Nastase might have taken his place among its long line of lovably eccentric kooks. As it was, he was thrown into the center of a gigantic new sports entertainment business, where serious money was on the line and the opportunities.to chase it were endless.

By the middle of the 1970s, Nastase's hair had grown long and wild, and a patchy black beard often covered his face. He wasn't always so lovable, either. He stalked the court with campy menace, the wires of his nerves sizzling, always on the brink of another rococo rant.

The sport was testing its limits--and Nastase's. Tennis was no longer a summer idyll. In the American empire, tournaments were run for profit, at the largest venues possible, and promoters competed for the services of star players.

The tour, with no single governing body, became a boundless, airless circuit of player lounges, indoor stadiums, hotel rooms, and airports. The pro game would soon be played every week of the year.

By the end of the decade, the men wouldn't even be able to fit their season into a single calendar year. Indeed, the Masters, the tour's version of the World Series, took place the January after each season, at Madison Square Garden.

Nastase had been a transitional figure and a guinea pig in this shift, an inmate of the amateur game and Communist Romania who was given a chance to run the asylum as a star professional.

But as the 1970s gave way to the '80s, he had become a trendsetter in another way. By 1981, he was, by all appearances, "burned out."

This would become a fashionable phrase of the era, in tennis and in other professional sports, as the mercenary grind of big-money athletics began to take its toll on its performers. Sports such as tennis, which had exploded so colorfully and lucratively in the 1960s and 1970s, were an entrenched industry now.

Talented kids were slaving at them full time by age 10. In 1980, 16-year-old Jimmy Arias had made his U.S. Open debut. He was the first product of the Nick Bollettieri Tennis Academy, a boarding school/tennis factory/boot camp in Bradenton, Florida, where children were drilled for hours in the hopes of someday securing jobs-as professionals.

Soon copied worldwide, Bollettieri's was the next step in tennis's evolution from the professional to the industrial. The academy was eventually bought by IMG, which added separate boot camps for golf, baseball, basketball, and soccer.

Tennis led the way: among young women pros over the next decade, "burnout" would almost come to seem like a treatable medical condition.

As Nastase arrived in New York for the 1981 Open, the years, the rants, the flights, the fame, the sex, the round-the-world chase after the next buck-all had left him a shell of his former self.

The man who had been the first number one on the ATP's computer rankings eight years earlier had drifted down to an inconsequential number 78. He had been dropped by his agency, IMG.

He hadn't reached the final of a Grand Slam in five years, hadn't won one in nine. In fact, he hadn't won a tournament of any sort since 1977, and at the start of 1981 he was barred from playing Davis Cup for Romania.

The wins may have stopped, but not the antics. At 35, Nastase's physical decline was inevitable. But along with his game, he had also lost his nature boy's love for playing and performing.

Some of his colleagues on tour thought that the mad Romanian, who had always flirted with the emotional edge, had finally "gone off the deep end," that his famous nerves were shot.

He showed up at tournaments with just two racquets, of different makes. He lost first-round matches to nobodies. Afterward, he repaired to the darkness, and the soothing TV set, of his hotel room.

His friends had begun to worry about his health. One of them, his frequent partner in crime Jimmy Connors, had tried to help by inviting Nastase to practice with him in Florida. Nastase, too proud, declined.

Booked to play tournaments or exhibitions for 47 weeks in 1981, he couldn't get off the endless circuit that had come to be his life, even as it was draining him. "If I stay somewhere two weeks, I go crazy," he claimed. It was, as one Nastase watcher said, "the itinerary of a homeless man."

Two days before his first match at the Open, he defaulted the final of a tournament because he had already committed to playing an exhibition the same day somewhere else.

Press sightings of Nastase didn't do much to reassure anyone about his state of mind. A March1981 Tennis magazine article entitled "The Tragic Twilight" found him in a Memphis hotel room after another first-round loss, preoccupied with a novelty clock he had bought on the street.

"It's fantastic," Nastase said, sounding more cheerful than he would the rest ofthe afternoon. "I can't stop looking at it." He wrenched himself away long enough to say, "Tennis is a very dangerous life…but what can I do, kill myself?"

Tennis Week's Linda Pentz met a similarly morose Nasty a few months later. "I don't enjoy it like before," Nastase said on the eve of the U.S. Open. "The day I don't enjoy it I will stop. Maybe tomorrow."

He wasn't too sanguine about the state of the sport, either; even the way it was scored annoyed him now. "The game is boring anyway so I guess it's going to get much more boring."

Nastase was reeling. His personal life had unraveled in a painful and public way over the last year. His thoughts were never far from the drawn-out divorce proceedings taking place between him and his wife, Dominique.

"Tennis cost me my family because it isn't a normal life," he told Pentz. "To spend nine years with a person and to have a child, to lose them because of a game is a big, big price to pay.”

"I have a couple of friends, a couple only, that's it. I always feel you are never happy. If you have $100, you want $10,000.”