Playing the Greats:

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

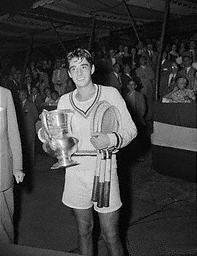

Pancho, age 20, after his first U.S. Championships in 1948. |

Pancho Gonzales was, arguably, the greatest player of all time. His career at the top lasted an incredible number of years.

He won the US Championship at Forest Hills in 1948 at the age of 20, entering the world's top ten for the first time, and was ranked number six in the world in 1969 before finally exiting the top ten 21 years later. Pancho won the US Championship again in 1949 before turning professional in 1950.

With Jack Kramer's retirement, Gonzales became the best player in the world in 1954 and fended off all challengers on head to head and round-robin tours for the next ten years where he defeated Ken Rosewall, Lew Hoad, Malcolm Anderson, Alex Olmedo, Ashley Cooper, Frank Sedgeman and Tony Trabert.

During that period he won the US Professional Championship tournament eight times. He finally began to slip in the mid-sixties, relinquishing his number one position to Rod Laver, but remained a dangerous opponent for anyone in the world until the early 1970 's.

What can we learn from the career of this incredible performer? Possibly that superb athleticism, fiery desire, and iron will can overcome technical stroke deficiencies.

|

Pancho's career as a top player had an incredible duration of over 20 years. |

Although Pancho's game was on the way down by his early thirties (most players peak in their late twenties), his late results give us an idea of how great he must have been at his zenith.

At the age of 43 he won his last Open tournament at Des Moines . In 1968 at the age of 40 he reached the quarterfinals of the US Open, defeating second-seeded Tony Roche (a finalist at Wimbledon ).

The next year he beat Charlie Pasarell (ranked #1 in the US in 1967) at Wimbledon in an incredible five-hour match played over two days, saving seven match points in the fifth set.

That same year he beat John Newcombe, Ken Rosewall, Stan Smith and Arthur Ashe (6-0, 6-2, 6-4) at Las Vegas , the second most lucrative tournament of the year. In early 1970, at nearly 42 years of age, the old man beat the world's number one, Rod Laver, in a $10,000 winner-take-all match at Madison Square Garden , to the delight of a crowd of 14,761.

Pancho was a greatest competitor I ever saw, though I never watched Jack Kramer or the players that came before him like Vines, Riggs, Perry, etc. But there was nobody in the last forty-five years better at winning than Pancho, including the likes of McEnroe and Connors, who resembled him in temperament.

Once Gonzales got an opponent down the outcome was assured. He was like an anaconda: after he got his teeth into an opponent, escape was virtually impossible.

Although I am sure it must have happened from time to time, I never personally witnessed Gonzales lose his serve when he was serving for a set or a match. At the finish he took his time, he looked across the net with blazing eyes and ferocious resolve.

Here, his first serve went in with uncanny frequency. Like the other champions of his time, he followed it to net where he was, with his incredible athletic ability, size, and speed, able to reach all but the greatest passing shots.

Pancho's volley was flawless. His hands were soft and secure, much like McEnroe's, and his nerves were steely calm under pressure. In the clutch Pancho simply did not miss.

Pancho was one of those rare individuals who could actually play better when he got mad. Lots of people think they can but few actually do. When the ordinary mortal becomes angry his judgment clouds, his hands stiffen, his patience evaporates, and he loses. He may make some great shots and play streaks of inspired tennis, but these interludes are adulterated and ultimately undone by errors.

This was not the case with Gonzales (nor was it the case with Connors or McEnroe in their primes). Anger simply motivated Gonzales. It increased his adrenaline and made him more alert, quicker, stronger, and more focused on winning than ever. He became meaner and more menacing.

Compared to Gonzales, Connors and McEnroe were pussycats. Gonzales was much bigger, had a nasty-looking scar across one side of his face and, when riled, his eyes flashed, his expression darkened and you got the nasty feeling that he was about to hurt you.

Pancho came from the rough part of town and was known to have gone into the stands after spectators that annoyed him. He was scary. And, to the consternation of his opponents, Gonzales was easily angered. His rival and friend over the years, Pancho Segura, pegged him right when he said of him, "Gonzales is very even tempered. He is always mad."

My first experience with Gonzales' temper was in the late 1957 at the Pan Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles where he was playing Lew Hoad on their head to head world tour. I was eighteen at the time and had gained free admission by agreeing to call a sideline.

In the middle of the match I made a close call against Gonzales. With explosive violence he whacked a ball into the backstop near my head, glared at me and growled threateningly "Watch that fucking line better." That straightened me right up. I don't know whether I made a bad call on that ball or not, but you can be sure I wasn't about to call another ball against Gonzales unless I was dead certain.

On the professional tour in the 1950's and 1960's Gonzales was a loner. He had the personality of a timber wolf. Unlike other players who were generally sociable and enjoyed the each other's company, Pancho kept to himself. He was a brooding, antagonistic, and contrary individual, feuding with tennis associations, promoters, opponents, and spectators alike.

He was in trouble from the beginning of his career, having run afoul of Perry T. Jones, the czar of Southern California Tennis during the time he was an amateur. Perry Jones insisted all junior players under his tutelage complete high school. Gonzales was more interested in racing cars and playing tennis and quit school anyway.

Jones banned him from junior tournaments. But genius can not be denied and Gonzales, after sitting around for over a year, came of age, was able to escape Perry Jones by competing in the men's division, winning the US Championships a couple of times before turning pro.

Pancho Gonzales was, arguably, the greatest player of all time. He was a beautiful athlete, about 6'3", but looked even bigger. He had long arms and legs and moved with marvelous speed and grace. His reputation was as a huge server, but in reality, Gonzales was a "touch" player. He won by running down everything and rarely making mistakes.

|

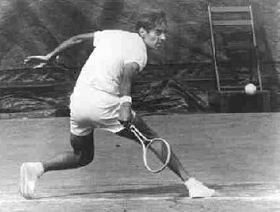

| Pancho beat you as much with his volleys as with his serve. |

Pancho had wonderful control and an instinct for putting the ball in awkward positions for his opponent. If you watched him play at a distance, you could have mistaken him for Ken Rosewall because his movements were so quick and effortless. He had perfect balance, never seemed rushed, and changed directions like a cat.

As was typical of his era, Pancho served and volleyed. He relied on holding his own serve indefinitely while making his opponent work for every point to hold serve.

Pancho had a powerful forehand and a consistent slice backhand. The backhand passing shot was Pancho's only weakness. Because he came under the ball, against a volleyer, he could only dink it crosscourt, lob, or hit relatively hard up the line.

Pancho returned serve very well with his backhand, keeping the ball low, and rarely missing. The volleyer did not have to worry about getting passed on Pancho's service return, but he was surely going to have to hit a low volley. Soft as it was, this ball was very difficult to put away, particularly since Pancho ran like a gazelle.

A wise opponent would hit this shot back deep to Pancho's backhand and a little game of cat and mouse would ensue, with Pancho chipping, lobbing, running, and smacking the occasional down-the-line passing shot.

Sometimes Pancho would come in on his serve return and try to pick his opponent's volley off out of the air so there was never an opportunity to relax. If the opponent was sure-handed and quick he could hold serve relatively consistently, but it was physically demanding and mentally wearing.

Meanwhile, Pancho kept a death-grip on his own serve. Eventually Pancho's opponent would make a few mistakes, Pancho would knock off a couple of passing shots and it would be over.

Pancho did not excel just because of his superior athleticism. He loved to play the game and spent a great deal of time on the court.

I first met Pancho when I was 17 years old (in 1956). As one of the better juniors in Southern California , I used to work out at Hillcrest Country Club where my good friend, Carl Earn, was the pro. Carl, who was in his mid-thirties at the time, had toured on the pro circuit with Don Budge and Welby Van Horn and still liked to play. He was a lively and funny character, and I used to practice with him often.

One day Gonzales came by and Carl asked him if he wanted to play a set with me. "Yeah", he said, and we went at it. I won the first few games because Pancho wasn't warmed up (or really trying) and Carl started kidding him about losing to a junior. Pancho snarled, turned on the juice, and won the next six games.

The interesting part was that Pancho Gonzales, the best player in the world, loved the game so much, in his spare time he was happy to get on the court with a junior. That doesn't happen much today.

|

In his 30's and 40's Pancho still loved to play the game. |

Year's later Pancho was as keen to play as ever. In 1966 I was working out at the Los Angeles Tennis Club to get ready for the Pacific Southwest tournament. In those days I was one of the better players in the United States and was capable of giving Pancho a tough match in practice (although in a tournament I could not have beaten him).

Since I was the best player in town at the time, we played, at Pancho's insistence, three out of five set matches every afternoon, with the loser paying for balls. (As an indication of how much the game has changed, here was one of the best players in the world actually motivated by the price of a can of balls!) Our matches usually lasted over three hours and the 38 year-old Gonzales had already played an hour or two in the morning, to boot.

Pancho was still a ferocious competitor but was starting to mellow just a little. As an example, in one of our matches I supplied a can of Spalding balls to start with. The first set went back and forth, and when I won it Pancho let out a roar, " These God Damn balls aren't true," and smacked all three of them over the fence. He claimed they were unbalanced and did not fly straight and refused to play until we got a new can of Wilsons .

The second set was particularly gruesome since Pancho was still stung from the loss of the first. He glowered, cursed and smacked the occasional ball into the fence, all the while playing better and better as he became madder and more vicious.

Finally, he got the upper hand late in the set and as we changed sides he snarled, "How would you like to play a son of a bitch like me three out of five sets on CLAY?" I thought I detected a twinkle in his eye when he said it and for the first time I could remember, Pancho actually seemed to be making subtle fun of himself.

Years earlier his nasty remarks were meant to have more sting, although he was such an idol to me I was just happy he was talking to me at all. At one time I asked him where he got that long scar across his face. "From asking too many questions! " he replied, glaring at me. I wasn't sure if he was kidding but I shut up anyway.

Another time we were practicing and I was giving him a closer match than he thought I should. I hit what I thought was a clever angle volley winner and he shouted at me, "You can't break a fucking egg with your volley, just like Tony." He was trying to insult me, but by Tony he meant Tony Trabert, whom I thought was a great player, so I considered it to be a compliment.

Notwithstanding the occasional outburst, playing Pancho was fun. He didn't hurt you too much on your own serve so you could usually get into the match. He relied more on consistency than power, more on wearing you down than blowing you out, so you were able to develop rhythm against him. If you didn't miss many volleys you could hold serve with some regularity.

Breaking his serve was the problem. His height and fluid action allowed him to ace you with big, wide, flat serves. His second serve was generally a heavy, deep kick, although he could slice wide to the forehand when he wanted.

|

Passing Gonzales was very difficult and he could put his volley anywhere. |

But Pancho beat you with his volley more than his serve. Instead of hitting the big first serve all the time he mixed it up with slices and kicks. This increased his percentages and kept you off balance. You had to always be alert for the big one and this made his spin serve more effective.

His volley was so good he didn't have to ace you. Once he was established at net, passing or lobbing him was extremely difficult. Only the hardest hitters could get the ball out of his reach, and if Pancho reached the ball he could volley it anywhere.

How good was Pancho compared to the other tennis greats? I think it depends on his opponent's style of play and the surface. He was certainly among the best I have ever seen. In 1971, at the age of 43 he beat 19-year-old Jimmy Connors (certainly several years before Jimmy's prime but many years after Pancho's) in the finals of the Pacific Southwest Championship, and he killed a mature Ken Rosewall in a head to head tour.

Pancho is the only player I would have bet on against the great Borg on clay. Borg wore opponents down on clay but did not volley well, and if you did not come to net against Pancho, you could not exploit his lone weakness - the lack of a strong backhand passing shot. Borg would have had to run on the baseline with Pancho, and Pancho's sliced backhand was very efficient and physically easy to hit.

Borg's topspin shots, in contrast, took a lot of effort. Pancho was also fast, relentless, and could run with anybody. Ultimately, Pancho could have picked his spots and come to net to finish Borg.

On the other hand, Pancho would have had a lot of trouble, on a fast court, against McEnroe or Sampras, both of whom had great volleys and could have attacked Pancho's backhand at net behind their serves, and both of whom could hit passing shots hard enough to pass Pancho.

|

Pancho could run with anyone and his slice backhand was efficient to hit. |

In his later years Pancho mellowed considerably, becoming almost gentle. In case you can't tell by the way I have talked about him, I idolized, loved, and profoundly respected the man. Like most of the great players, he was very intelligent, direct, and honest. If he told you something it was certainly true.

At one time I asked him if he would be willing to take a personality test I was administering as a research project to see how great players compared, mentally, to ordinary people. Pancho said he didn't have time to take it on the spot, but he would take the test back to Las Vegas , fill it out there, and send it to me. The test required over an hour to complete and, true to his word, Pancho took the time to fill it out and return it to me.

In his 60's he married Rita Agassi, Andre Agassi's sister, and Pancho's sixth wife. With her he had a son, Skyler, who was the apple of his aging eye. Every time I saw him, in those later years, he told me stories about what a talented tennis player young Skyler was. On one occasion I could not resist teasing him and said, "Of course Skyler is a great athlete. He has Andre Agassi's genes." Pancho laughed. He was, by now, a far wiser and gentler old soul than the wolf I had known those many years ago.

Read More From Allen!

Visit him at www.allenfoxtennis.net

|

Winning may not be everything, but Dr. Allen Fox points out that, if we are honest with ourselves, winning is still eminently preferable to losing. In his new book, The Winner's Mind, Allen lays out an original step-by-step plan for succeeding at any of life's endeavors, based on his first hand and very personal observations of the careers of both world-class tennis players and successful businessman. The bottom line is that even if you are not a born champion--and only a tiny percentage of us are--you can still use the success strategies of champions to tilt the odds in your favor. Writing with brutal honesty and dry humor, Fox lays out the common mental characteristics of winners in sports and in life. He explains the critical role of intellect over emotion. He analyzes the struggle between ambition and fear and the insidious and pervasive fear of failure that undermines so many of us. He then outline how to confront and overcome these fears in your life and career, even when they are initially subconscious. Must reading from one of the great thinkers in tennis, and a Renaissance Man in life. Click Here to Order. To purchase this book you can also send a check for $17.95 to Allen Fox, 1120 Inverness Place, San Luis Obispo, CA. 93401. The price includes shipping. |

|

Allen Fox PhD is a former world class player, a coach, a psychologist, and one of the most original and insightful analysts in modern tennis. A top 10 American player from the glory days before Open tennis, Fox played many of the legendary greats, among them Roy Emerson, Rod Laver, Stan Smith, and Arthur Ashe. At Pepperdine he developed the men's tennis program into an elite contender for national titles, and gave Brad Gilbert the insights that became the foundation for "Winning Ugly". His book Think to Win is a modern classic. He has also starred in a series of acclaimed videos, including Pro Secrets of Match Play and Allen Fox's Ultimate Tennis Lesson.

|

|

Contact Tennisplayer directly: jyandell@tennisplayer.net

Copyright Tennisplayer 2005. All Rights Reserved.